Author: Brittany Pugh

Have you ever sat down to research a topic in science, typed your keywords into a research database and been greeted with paywalls, read-only PDF’s and having to endlessly type in your institutional login to check if what you thought was a promising abstract is relevant to your work?

In recent years, Open Access is a term that is increasingly being thrown around the research community, often stirring up contention, but what does Open Access really mean?

Before we go into its intricacies, or indeed its implications, we must first look at the history of academic publication.

The first academic journal ever published was the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1665 (Mudrak, 2020). From this point on, science had a platform for assessing its quality and disseminating its findings, accelerating the rate of scientific discovery. However, disseminating hard-copies of journals to an ever-growing audience comes at a cost, causing publication prices to soar over time. It would therefore be logical to expect these prices to have diminished alongside increasing digitization replacing hard-copies of journals during the 1990s.

Why then did publication fees instead rise 4 times quicker than inflation from the 1980s to now (Suber, 2015)? Why also, with high publication fees for authors do most journals still require readers to pay for scientific content? In a world facing many global challenges; climate change, pandemics, and widespread inequality to name a few, why do barriers to scientific research still exist?

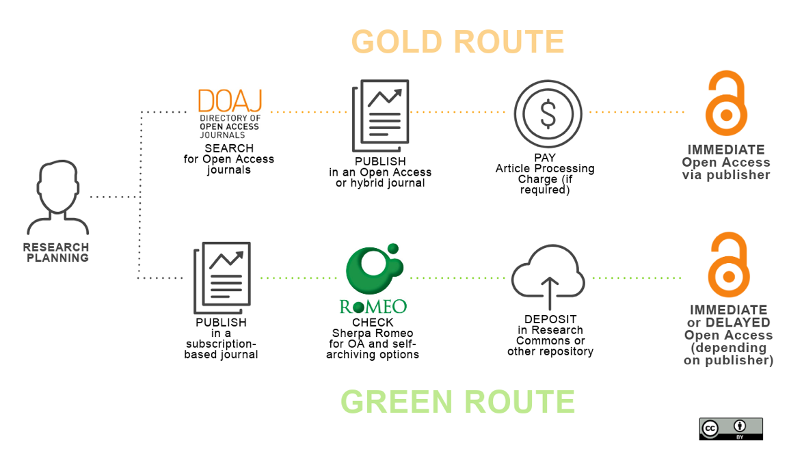

These questions form the crux of what those supporting Open Access are trying to answer and find solutions to. First defined in 2002 by the Budapest Open Access Initiative, Open Access now has a multitude of definitions and forms but can ultimately be summarised as data and publications which are free for anybody to use and download. Its aim is to improve global access to scientific knowledge, thereby accelerating scientific development. The main two forms of Open Access used by scientists are ‘Gold’ and ‘Green’ (Figure-2). Gold Open Access involves paying a higher Article Processing Charge (APC) to a publishing body. This allows authors to maintain the copyright for their articles and free access for readers to read and re-use work. However, Open Access APC’s are not cheap. Most journals, whether fully Open Access or ‘hybrid’, have an average Open Access APC of around $2000-3000 (University of Cambridge, 2018). Therefore, due to a lack of Open Access grants and funding, many authors instead publish via Green Open Access; paying a lower non-Open Access APC and putting a copy of their paper into an Open Access repository after an ‘embargo period’ stipulated by the journal they are publishing to. Therefore, delaying access to free research.

Steps are now being taken towards increasing Open Access. In the UK for example, the Higher Education Funding Council has requested that all institutional research published after the 1st of April 2016 is Open Access. Additionally, many tools and repositories have been developed to legally (or sometimes semi-legally) overcome paywalls and provide Open Access. For example, Sci-Hub, Unpaywall and Open Access Button. This aids all scientists, everywhere. Especially those in low- or middle-income countries who may be less able to pay lofty journal subscription charges, furthering equality in research.

However, despite this progress, scientific traditions still hold strong. Scientists looking to further their careers understandably still want to publish in ‘high-impact’ journals. The fallibility of research impact ratings is a topic for another day, but this pressure for ‘impact’ means that publishers still have power to resist the tide slowly moving towards full Open Access. This is because there is a distinct ‘hierarchy’ of journals based on impact rating, with the highest impact journals generally charging the highest APC’s. As well as this, nobody can deny that publication costs money. Therefore, what we really need is a new scientific publication model which allows Open Access for all research, a feasible economic model for journals and for those paying APC’s. This may not be easy to accomplish but with over 50 million academic articles in existence in 2009 (Jinha, 2010) and millions more being published each year, the need for Open Access and reuse licenses (so that research can be used in metanalyses) is increasingly critical.

Besides, when was science ever easy?

Figure 1: Source: Creative Commons, 2016. The Open Access Logo.

Figure 2: Source: The University of Waikato, 2020. An overview of the two main types of Open Access.

References

Creative Commons, 2016. Open access logo. [Online] Available at: < https://creativecommons.org/about/program-areas/open-access/open-access-logo/ > [25/5/20]

Jinha, A., 2010. Article 50 million: An estimate of the number of scholarly articles in existence. Learned Publishing. 23: 258–263. https://doi.org/10.1087/20100308

Mudrak, B., 2020. Scholarly Publishing: A Brief History. [Online] Available at: < https://www.aje.com/arc/scholarly-publishing-brief-history/ > [25/5/20]

Suber, P., 2015. Open Access Overview. [Online] Available at: < http://legacy.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/overview.htm > [25/5/20]

University of Cambridge, 2018. How much do publishers charge for open access. [Online] Available at: < https://www.openaccess.cam.ac.uk/publishing-open-access/how-much-do-publishers-charge-open-access > [25/5/20]

University of Waikato, 2020. Open access. [Online] Available at: < https://www.waikato.ac.nz/library/study/guides/open-access-information > [25/5/20]