Author: Rio Kevin

Institution: Physics

Date: June 2007

MDMA, more commonly known as ecstasy, has rapidly become one of the four major illicit drugs in the U.S.,along with marijuana, cocaine, and heroin. During the 1990s, its use spread from the rave subculture to a more general high school and college audience. Despite its reputation as a relatively benign drug, data from animal and human studies suggest that MDMA may cause brain damage after just a few doses,unlike 'harder' drugs like cocaine and heroin, which take years to damage brain tissue.

MDMA Basics

MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine) is derived from amphetamine, a psychomotor stimulant. Its effects are significantly different from most stimulants; in fact, they are quite unique. Taken orally or insulfated (snorted), MDMA works by causing a surge in the release of several neurotransmitters,chiefly serotonin but also dopamine and norepinephrine,that regulate the neuronal circuits for pleasure and emotion in the brain.

Recreational users take MDMA for its subjective effects,which include euphoria, empathy, and heightened emotion and openness. It is not surprising that many psychiatrists were once interested in the drug as a supplement to psychotherapy,perhaps it would allow clients to speak their minds more freely? Despite these potential benefits, the toxic effects of the drugs make this practice simply too dangerous.

MDMA also causes a wide variety of temporary physiological changes, which most users would consider side effects. These include dilation of the pupils, increased heart rate and blood pressure, loss of appetite, and dehydration. This last effect is particularly dangerous. There have been several reports of teenagers and young adults dying of dehydration after a night spent dancing a rave party on ecstasy.

MDMA tablets for oral consumption. Image courtesy: erowid.org

Neurotoxicity in Animals

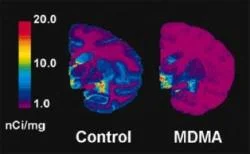

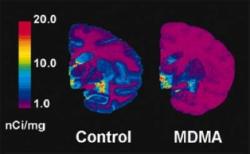

MDMA's effects in animals, particularly rats but also monkeys and some other mammals, have been well studied. A consistent finding is that MDMA reduces overall functioning in serotonin neurons,the same neurons it acts upon to produce its pleasurable effects. It is as if the drug "overloads" the brain's circuitry with a flood of neurotransmitters, which have toxic effects. This damage does not appear to be reversible and can have serious long-term effects, including an increased susceptibility to depression.

As with most MDMA research, even these well-established conclusions are questioned. A study by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) recently suggested that doses that cause serotonin depletion "do not reliably increase markers of neurotoxic damage such as cell death, silver staining, or reactive gliosis." The study did not vindicate MDMA altogether,it also found that administration of the drug could produce persistent anxiety even in the absence of measurable cell damage.

SERT (serotonin neuron) density measured by PET scan in baboon brains. The baboon on the right was given a neurotoxic dose of MDMA a year before the scan; the control baboon was given a placebo. Image courtesy: DEA

Neurotoxicity in Humans

What MDMA does to rats is of little concern to most people outside the scientific community. While we may be able to glean some insights into the drug's affects from animal studies, the public rarely takes notice until evidence in human trials comes to light. Hundreds of reports over the past decade or so suggest that MDMA causes serious and long-lasting brain damage in humans.

A recent study conducted at John Hopkins University used PET scans to examine specific nerve cells in the brains of human MDMA users. "We had long suspected MDMA was dangerous, based on our earlier studies in primates that showed nerve damage at doses similar to those taken by recreational drug users," says neurologist George Ricuarte, principal investigator. "But this is the first time we've been able to examine the actual serotonin-producing nerve cells directly in the brain." Serotonergic damage was greater among MDMA users than in a control group, and the amount of damage was proportional to the number of times users had taken the drug.

Researchers at the University of Toronto found that prolonged MDMA use led to memory loss in human subjects. The drug affects the hippocampus, a portion of the brain involved in consolidating memories from short- to long-term. This damage resulted in cognitive decline, particularly in retrospective memory,the ability to recall a short passage immediately and after a delay. "For those who use ecstasy repeatedly, there is preliminary evidence to suggest memory processes can be impaired with continued use of the drug," says Konstantine Zakzanis, co-author of the study.

Particularly frightening is MDMA's ability to cause brain damage during the first or second recreational dose. After numerous animal studies, the first paper to examine these effects in humans was published in 2006 and presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA). Subtle, but measurable, differences in brain chemistry were observed in first- or second-time users,including decreased blood flow to certain areas of the brain and changes in cell architecture. It is still unknown whether these changes are permanent or not.

The Future of MDMA

Despite these somewhat grim reports, many remain unconvinced that MDMA is dangerous in humans. The Lancet, a leading medical journal, recently published an article from UK researchers that suggests MDMA is one of the least dangerous illicit drugs for human consumption,ranking below alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana.

The report has been criticized by many in the scientific community. In particular, its definition of "dangerous" has been called into question. The study's findings are based on surveys filled out by drug 'experts,' among them doctors, pharmacologists, and law enforcement agents. To a police officer, MDMA would seem relatively harmless,it does not make users violent (like methamphetamine or cocaine) and it is not so exorbitantly expensive that its users must resort to crime to support their addiction (like heroin). Simply because MDMA does not pose much risk to non-users does not mean it should be considered safe.

A highly controversial ranking of licit and illicit drugs, from "most dangerous" on the right to "least dangerous" on the left. Note that MDMA (ecstasy) is among the least dangerous. Image courtesy: The Lancet.

Although there is no smoking gun to prove that MDMA is neurotoxic at the first recreational dose, evidence is mounting to that end. Users should be aware that MDMA, like any drug, is not totally harmless and can have serious side effects.

Maartje de Win, a radiologist at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, sums up the current state of MDMA research by saying, "We do not know if these effects are transient or permanent. Therefore, we cannot conclude that ecstasy, even in small doses, is safe for the brain, and people should be informed of this risk."

With hope, this information will trickle down to the teenagers and young adults currently using or thinking about using MDMA. Whether or not they choose to take the drug is an individual decision, but they should at least be aware of its potentially dangerous consequences.

References:

"Hopkins study shows brain damage evidence in ecstasy users" from Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions (http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/1998-10/JHMI-HSSB-301098.php)

"Study finds long-term ecstasy use leads to memory loss" from the American Academy of Neurology (http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2001-04/AAoN-Sfle-0904101.php)

"Ecstasy can harm the brain of first-time users" from the Radiological Society of North America (http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2006-11/rson-ech112106.php)

"Alcohol and tobacco cause more harm than ecstasy, study claims" by David Rose, The Times (UK).

- Written By Kevin Rio.

- Reviewed By Antje Heidemann.