Author: Doshi Ojus

Date: February 2007

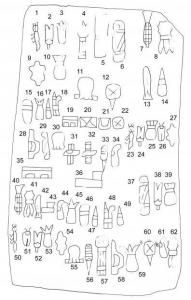

Insect, dart tip, corn, corn, throne, beetle, shucked corn.

Vertical fish, eyes, skin, bivalve..and corn.

Huh?

That's what anthropologists and archaeologists alike are asking after the discovery of the Cascajal Block, an ancient slab of writing which is thought to be the oldest known writing system in the Western Hemisphere. The block features linear arrangements of certain characters that appear to be ancient depictions of tribal objects, such as animals, insects, tools and food (especially corn). A team of anthropological researchers announced the find in the journal Science last month. Determined to be from the Olmec civilization, the block dates to the first millennia BC according to the lead researchers and was found in Veracruz, Mexico.

The intrigue of the block lies in the writing system, a hitherto unknown way of communication for the Olmecs of ancient Mesoamerica. "It's showing that they're literate," explained Dr. Stephen Houston, a corresponding author of the paper and a professor of anthropology at Brown University. "With literacy, you can compile records or communicate over long distances, without any miracles of memorization."

The actual language on the block, however, is currently untranslatable. But it gives new dimension to a relatively unheard of civilization which came before the more popular Mayan and Aztec tribes.

The Olmecs

The Olmecs, regarded as America's first civilization, existed from about 1500 to 400 BC. They resided in what is known as "Olman", or the Olmec heartland, situated in Mexico on the southern tip of the Gulf of Mexico. It stretched from Veracruz in the west to Tabasco in the east, occupying the northern part of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

"The land is extremely rich," mentioned Houston. "They grew four crops of maize without irrigation."

Surrounded by mountains, their land was abundant in bodies of water, with various rivers and streams running through the heartland. Rain was plentiful, the air was humid, and the temperature remained between 68º F and 86º F. The fertile land also provided an excellent environment for many forms of wildlife and plantlife.

The Olmec are well known for their gigantic sculptures, particularly their colossal stone heads. The colossal heads are thought to depict important Olmec men, such as rulers or maybe sports players, and look very realistic. Constructed from boulders, all heads included a different headdress which may have identified the status of the men depicted in the sculpture.

Furthermore, the Olmec produced a prodigious amount of small ornaments and figurines which resemble the look and are mistakenly labeled jade.

The larger Olmec villages consisted of mounds which served as dwellings for the higher ranked families. The mounds, when placed at a higher elevation, protected the inhabitants from the flood waters that often engulfed villages. Other families built lean-to houses replete with gardens, courtyards and fences.

Maize was the staple crop for the Olmecs. The wild strains of maize fit the climate and soil of the Olmec heartland well, and the food was used on a daily basis and as the primary feast food. Improvisation led to a large variety of corn-based food, such as flat corn cakes made from maize dough. Maize's importance was reflected in depictions of some religious icons or gods, some of which have cobs and leaves as head pieces.

Evidence has shown that higher ranked Olmecs may have also enjoyed atypical foods like deer, crocodile and dog meat.

Caption:Frontal view of Cascajal block, Veracruz, Mexico. Credit: Image (c) Science

From all the iconography that has been found,large monuments, smaller figurines, etc.,the Olmecs certainly had a religion. "Religion was the force that bound Olmec culture together," remarks Dr. Richard A. Diehl, anthropology professor at the University of Alabama, in his book The Olmecs.

The religion was polytheistic with deities such as The Olmec Dragon, Bird Monster, Fish Monster, Water God, Maize God and Feathered Serpent. The agricultural and fertility gods played a prominent role among the others, according to Diehl.

The Olmecs performed religious rituals in temples, courts, caves and mountaintops. There are theories about priests and shamans and what their exact duties were. It also seems that rulers had some kind of connection to gods that kept them in elite status.

Relatively little was known about Olmec language and writing before the discovery of the Cascajal block. The Olmec certainly had symbols: "It's the first group of people to have elaborate symbolism," explained Houston. In 2002, a roller stamp and fragments of a plaque were found in San Andres, Tabasco, which dated to at least 650 BC. They also had a calendar system, but there is limited evidence to describe the system in detail.

The Cascajal Block

The find in Veracruz seems to indicate that the Olmecs were writing long before the San Andres roller stamps existed. "The block is clearly centuries earlier than any other known written artifact," said Houston. "There are some examples from the Maya which date to around 300 BC and the valley of Oaxaca which date to 500 BC."

The block measures to over a foot in length and is about the size of a small flat screen TV, but much thicker. It features 62 symbols arranged in linear patterns on one side of the serpentine slab. The written side is clearly indented, for which researchers offer several theories.

"The indent on top is thought to be similar to an erase-a-sketch," remarked Houston. The researcher's report imagined an Olmec using a rock to grind away the existing writing incisions and start fresh on a smooth piece of rock.

Caption: Side view of Cascajal block, Veracruz, Mexico. Credit: Image courtesy of Stephen Houston

Another theory points to weathering. "Maybe they wanted it to be like that to protect it from being eroded," Houston mentioned. He gave an example of another rock sliding past the written surface but failing to mark any of the writing because of the indent.

But why do the researchers think the block depicts a writing system? "It's a codified system of signs," said Houston. "It has long linear sequences, which is what you expect from writing. It has all the earmarks of writing as we know it."

Clearly pictorial in nature, the several signs looked like common objects or animals,corn, fish, and insects. Others are more abstract, such as signs resembling a pair of eyes and other facial markings.

Figuring out what "insect, dart tip, corn, corn" means, however, is extremely difficult, according to most of the researchers.

"To decipher an ancient writing system, you're best off if you have a bilingual system," said Dr. Michael Coe, a Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Yale and Curator Emeritus of the Anthropology Department at the Peabody Museum. He cited the example of the Rosetta stone, an ancient slab with the same text written in Greek, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Demontic.

"[The Cascajal Block] is the only one example that has a text on it. If you've only got one example, you can't decipher it. I don't think it will ever be cracked,people were digging extensively and this is only one that has come up," he said.

Still, the block offers a few new insights about Olmec writing. Houston, who helped decipher Mayan writing, maintains that to make headway of an unknown language, pattern detection is a valuable tool.

"In the Cascajal block, there are patterns that are evident. (The Olmecs) are clearly being motivated by something grammatically," he said.

Houston also used pattern detection to hypothesize about the nature of the entire set of symbols: "It's not clear to me that it's an economic document because you would expect to find number-like symbols. Identifying numbers is not really a problem, but there was nothing like that, so it's about quantifying things. Some of the signs seem to be ritual implements."

The main controversy lies in the age of the block. It was originally discovered by construction workers and developers that had dug through a mound. Several clay shards and small artifacts lay very near the location of the block.

The authors of the report and principle researchers involved with its analysis concluded that it originated between 1100 and 900 BC, based on the fact that clay shards found around the block also date to this time.

"Generally you rely on context," said Houston. "The problem with this block is that it was not found in controlled excavations. We don't know where it came from in terms of levels of the sites."

Professor David Grove, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, finds these facts troubling. He has commented that he doesn't feel the clay shards qualify as contextual evidence and that the block is therefore dated incorrectly.

"I feel the block is a couple of hundred years younger than suggested in the Science article. I think it more likely dates to sometime between 700-500 BC," he mentioned. "I say that because in my opinion, some of those symbols only occur late in the Olmec period."

Overall, all researchers involved with Olmec or Mesoamerican study agree that the discovery and existence of the Cascajal Block is of major importance to history of the Olmecs and the history of language in the Western Hemisphere.

"It's important for two reasons," said Coe. "One, it establishes that the oldest civilization in that part of the world could write. Two, it's an entirely new system of writing,later writing systems don't look like it at all."

"It's a tantalizing discovery," Houston remarked. "I think it could be the beginning of a new era of focus on Olmec civilization."