Author: Erkenbrack Eric

Institution: Philosophy/Biology/German

Date: July 2006

Most of us learned about the planets not by looking up into the heavens, but rather by absorbing that highly retentive mnemonic: My very eager mother just sent us nine pizzas. Then we took a quiz and,some of us, at least,received cute drawings, smiley faces, stars or some other form of positive, or even negative, reinforcement.

But who decided those were planets, anyway? In fact, it appears that deciding which objects are planets and which objects are asteroids is a difficult question with no obvious solution. What's at stake here is not only the planethood of familiar objects like Pluto, but also the definition of the word itself. As it stands, recent findings are placing the mnemonic in jeopardy and engendering a partisan atmosphere in some circles of planetary science.

Figure 1. The fading definition of planet

If you think it's trivial to ask what a planet is, frankly, you may be right, and many scientists would not hesitate to agree with you. There are, however, some individuals in planetary science wanting to see the issue finally resolved. The quibbling and caviling is hopefully temporary, as a group of scientists from the International Astronomical Union (IAU) have recently formed a committee charged with settling on a scientifically acceptable definition of the seemingly elusive word planet'.

Figure 2. An icy rock or an object worthy of planethood'? An artist's rendition of the view from distant 2003 UB313. Image credit: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

The impetus for this international reaction was the publication of data confirming that trans-neptunian object 2003 UB313 is, in fact, larger than Pluto, according to a group of scientists led by astronomer Frank Bertoldi. From a reasonable and yet illogical point of view, 2003 UB313 should not be a planet. (Think of our precious mnemonic!) Thus the scientists arrive at a crossroads where they must play arbiter between tradition and discovery.

As we shall see, the dilemma is vexing and deeply-rooted in the history of discovery itself.

History: The Monkey on Pluto's Back

Percival Lowell was an ambitious man. He was well-educated, traveled all over the world conducting business, and in his later years whole-heartedly took up astronomy. For Lowell the big news was the only news,extraterrestrials on Mars, comets, trans-neptunian planets,and he conducted his research accordingly.

It was the ever-prescient Lowell who, wanting to account for the then obvious perturbations in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune, postulated the existence of a trans-neptunian planet, which he dubbed Planet X. Lowell died in 1916, but his ideas persisted.

The search for Planet X,the torch being carried by many of Lowell's former colleagues,continued in earnest at the observatory he founded in Flagstaff, Arizona. And in 1930, Clyde Tombaugh, a 24 year old set to the task of examining photographs of the night sky, fortuitously observed a miniscule, blurry dot shifting across a few photographic plates. The search was over; here was Lowell's Planet X.

Figure 3. A young Clyde Tombaugh at the Lowell Observatory ca. 1931. Image Credit: New Mexico State University Library Archives

The properties of Planet X that could be thoroughly investigated at that time were very similar to the properties that Lowell had predicted. But some were not. In particular, Lowell had predicted the mass of the object at many times greater than that of the Earth's and at the eccentricity lower than Mercury's,thereby affording it planetary status.

Thus by calling the object Planet X, it seems Pluto was a planet before it was even found. When Tombaugh made the fascinating discovery, all that was left, one could say, was the paperwork.

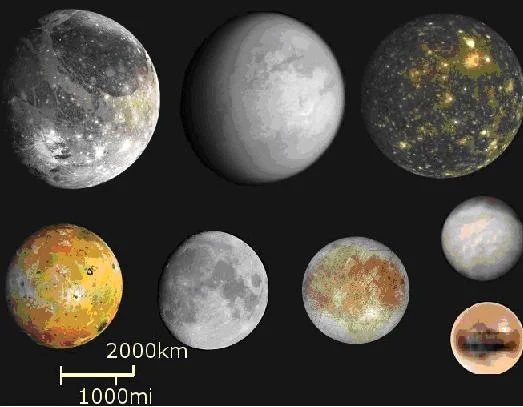

The calculation of Pluto's mass had to wait for the discovery of one of Pluto's companions, Charon, 48 years later. Before this, observations and speculations had dwindled the mass of the tiny planet to sub-Earth size, but very few if anyone was expecting Pluto to be dwarfed by our satellite (and, for that matter, many other satellites in the solar system). Some scientists, consequently, began questioning Pluto's status as a planet. But that was just the beginning.

Figure 4. Sizing up Pluto: major satellites of various planets in the solar system. From left-top: Ganymede (Jupiter), Titan (Saturn), Callisto (Jupiter); from left-bottom Io (Jupiter), The Moon (Earth), Europa (Jupiter), Triton (Neptune), Pluto (lower). Image Credit: NASA Jet Propulation Laboratory

"In 1992, objects started to be discovered in the Kuiper Belt, a belt of icy objects," describes Scott S. Sheppard, research fellow at the Carnegie Institute in Washington. "There are thousands of objects like Pluto in the Kuiper Belt."

Trans-neptunian objects are now commonplace. In fact, along the way, many new terms were coined to discuss these things,terms like plutinos', icy dwarfs', large minor planets'. The edge of the solar system was quickly eroded. One thing, at the very least, is much more lucid: the definition of planet is not so simple.

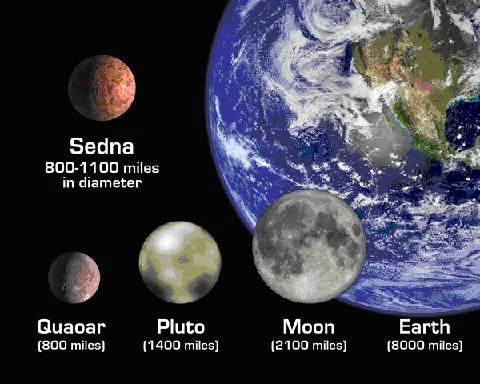

Figure 5. Pluto and other comparatively large celestial bodies in the solar system. Other noteworthys missing from image: 2003 EL61, 2003 UB313, 2005 FY9. Image Credit: NASA, JPL, R. Hurt

To date, four large minor planets have diameters estimated to be close to Pluto's (2,300 km), namely 50000 Quaoar (~1,200 km), 90377 Sedna (~1,500 km), 2003 EL61 (~1500 km), and 2005 FY9 (~1800 km). The most recent finding that 2003 SB313 is larger than Pluto has catapulted the dispute of planetary definition right back to the forefront.

A combination of raw jubilation during Pluto's discovery, Pluto's own peculiarities and exciting trans-neptunian discoveries now seem certain to forever alter our mnemonic. Any suggestions? Believe it or not, I found some.

The Need for a Scientific Definition

"Mary visits every morning,just stays until noon, or what have you," jokes Brian G. Marsden, director of the IAU's Minor Planet Center at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Marsden has watched the drama in the debate unfold for well over 30 years,and with some chagrin. "It's really altogether quite a complex issue," Marsden adds, "[and for that reason] the IAU has not yet taken a stand on the matter."

The IAU is considering three variegated definitions of planet': (1) any object orbiting the sun and has a diameter larger than an arbitrary size is a planet; (2) any object that possesses a mass large enough to result in the stable, spherical form is a planet; and lastly (3) any object which dominates its immediate environment, meaning it exerts sufficient gravitational effects on its surroundings, is a planet.

These definitions proved wanting for many scientists at the IAU's last meeting, as no majority could be reached. The crux of the situation lies in the basis of the definition. Some scientists maintain that an arbitrary diameter size is not scientific at all; rather, it's historic. This groups contend that the ability to extrapolate back to the origins of an object, e.g. it was captured in the system as a comet or a free-floating body, it was formed via accretion, etc., is of central importance. On the other hand, some scientists, such as Richard Binzel, professor of planetary science at MIT, contends that "any definition you make is arbitrary. I think the historical basis" is as good as any other.

David Morrison, co-author of The Planetary System and collaborator with the IAU, prefers a historical-scientific definition which is "as consistent as possible with the 9 planets we have" and which doesn't add too many. Demarcating an arbitrary diameter of, say, 1000 km has "two great advantages: (1) it preserves the current nine; (2) the number of new planets is probably not huge."

"Just saying it's got to be Pluto and above is not satisfactory because that is not a scientific argument," retorts Marsden. "This all comes down to the idea that maybe really if we're going to discuss thing, we really should have a scientific reason for that. Pluto defines the limit for no scientific reason at all."

Instead, Marsden believes the word planet' should always take an adjective. He separates the solar system into three distinct groups: terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars), gas or Jovian giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune), and icy dwarfs (all the rest). This leaves us with 8 planets, two major groups, and a whole lot of TNOs (Pluto being one of those).

Marsden has no qualms with demoting Pluto to a minor planet. After all, "labeling Pluto as a ninth planet was a big mistake," he says. "At the time it was discovered, in 1930, it was advertised as being quite a big object, Earth size. [And thus] Pluto was treated by many people as the ninth planet." But not everyone is so quick to send Pluto to the semantics guillotine.

Figure 6. At a distant 14.5 billion km, Pluto and its moon, Charon, are captured by the Hubble Space Telescope. NASA describes this as the "clearest view yet of the distant planet." Image Credit: Dr. R. Albrecht, ESA/ESO Space Telescope European Coordinating Facility; NASA

"All of the science questions we're asking about Pluto , its surface, its atmosphere, its moons , are the same questions we ask about the other planets," comments Binzel. "The reasons we want to study it are the same reasons we want to study the other planets."

It's hard to disagree.

Of course, we must remember that the true concern here is not with the scientists, but with the public. When Marsden proposed designating Pluto the 10,000th minor planet in the solar system and thereby bestowing it with a "dual-citizenship" of sorts, there followed a public outcry consisting of concerned patrons and children sending letters to the IAU in hopes of curbing the drastic action. In fact, many planetary scientists I spoke to considered this debate "silly" and "not important." Though, even for scientists, there is something that can be taken from this.

"Almost anytime you attempt to classify something it runs into something else," elaborates E. Myles Standish of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech. The important thing is that "it's gotten people to think about this [and is something that was] never was addressed before. Things are going to have to change."

Inevitably, some people will not be satisfied when the IAU issues its decree. But it surely seems likely that we'll have to drastically alter our precious mnemonic. The question becomes How much?'.

As it stands, the definition of planet' is rather ambiguous and is contingent on different theories and viewpoints in planetary science. One thing is certain and rather unambiguous, however. We send rockets and elaborate instruments of all sorts to distant worlds. The elusiveness of defining planet' seems not to affect our ability to do that.

"My job at JPL is to know the orbits of the planets. If they're on my file, they're a planet," remarks Standish. It's arbitrary, but comforting.

Suggested Reading and Viewing

Hoyt, William (1980). Planets X and Pluto. The University of Arizona Press.

Littmann, Mark (1988). Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

A photojournal of the solar system presented by NASA: http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/index.html