Author: Williams Shawna

Institution: Biochemistry

Date: September 2005

This fall, Shawna studied immunology and the Turkish language and culture in Istanbul and at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey. Here, she takes us through her experiences during her fall semester in Turkey.

article_492_order_0

The ferry linking two continents across the Bosphorus strait takes 20 minutes and costs about forty cents. Thousands of people ride it every day, most of them casual commuters traveling between their homes in Asia and school or work in Europe. Even visitors like myself soon grow nonchalant about making two or three transcontinental crossings in a day, and yet that ferry seems to me a fitting metaphor for Turkey itself, a balance between developing country and modern nation, between East and West. Turkey's multi-faceted realities render generalizations meaningless, as I was reminded every time I tried to answer an e-mail from someone back in the States about "what it's like to be here in the wake of September 11." I know that because of the complexity of this place, any reasonably pithy answer I might give to this question must necessarily be inadequate.

But I should start at the beginning. I chose to study abroad during the fall 2001 semester on a whim-it seemed to be a good way to ward off senioritis. Of the study abroad programs affiliated with my college, the new one in Turkey was the most appealing to me as a science major for a number of reasons. Most notably, its mid-August start date made it compatible with my summer research in molecular biology and biochemistry, it had no specific academic prerequisites, and it would allow me to study a wide variety of subjects (including the sciences) while abroad. Other students chose the program in Turkey because of the country's rich history and corresponding archeological wonders, or because its proximity to the Middle East, Central Asia and Europe makes it a fascinating political study. Because of the versatility of the program, those who participated this year were a diverse mixture of classical literature, anthropology, political science, economics, and psychology majors.

Most of our group of 13 students and two professors arrived in Istanbul on August 14th, and my first impressions of the city were heat - about 90°, and humid - and size (12 million inhabitants). As the predominant business and cultural center of the region, Istanbul was passed up in favor of Ankara for the political capital of the new Turkish republic in 1923. Its long years as the imperial city are still in evidence, however. It was christened the capital of the East Roman Empire (Byzantium) in 330 A.D. by Constantine the Great and named Constantinople in his honor. In 1453, it was captured by the Turks and re-named Istanbul, becoming home to a long line of sultans until the 1923 exile of the last of those rulers ended the Ottoman regime.

In contrast to Orthodox Christian Byzantium and the Islamic Ottoman Empire, modern Turkey is a firmly secular state. The government, fearing a fundamental Islamist revolution, even prohibits women from wearing headscarves (which, when tied under the chin, cover the hair and neck as decreed in the Koran) in public buildings.

But this is only one side of the story. As Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the revered founder of the modern republic, put it: "We are similar only to ourselves" - not to Europe, Asia, or to the Middle East. In a recent Newsweek story (Zakaria 2001), Turkey was ranked the Muslim country that provides its people the most freedoms, but the government's long attempts to Westernize have presented some interesting conflicts. Democratically-elected parties which profess Islamic values are regularly banned from playing a role in the political process, but the government, far from being "secular" in the American sense of the word, directly employs all religious workers in Turkey and even controls the content of the weekly messages disseminated in mosques. Pictures of Ataturk, who died in the late 1930s, are startlingly ubiquitous in Turkey, perhaps as part of the state's campaign to ensure that Turks' first loyalty is to their country rather than to their religion.

article_492_order_1

We stayed in Istanbul for three weeks in an otherwise empty dormitory at Istanbul Technical University (ITU). In the mornings we attended 3 hours of Turkish class, in the early afternoons we listened to specially-arranged lectures on Turkish history, culture, politics, and economy, and in the late afternoons we usually had some sort of optional outing such as a visit to a Turkish bath, a scenic boat ride up the Bosphorous, or simply a lazy afternoon sipping tea at an outdoor café, all organized by the ITU international office. In addition to the two American professors who had come with us, and our Turkish language professor, the director of the international office and several ITU students were available to help us see the sights and adjust to Turkish life. Though we greatly appreciated the guidance, many of us also felt that it made our initial experience somewhat insular.

Our dormitory was fortuitously located just off Taksim, the Times Square of Istanbul. Frequented as much by Turks as by tourists, Taksim is a haven for shopping, restaurants, and nightlife. A short bus ride away was Sultanahmet, a neighborhood rich with famed historical monuments such as Topkapi Palace, long the seat of the Ottoman government, Aya Sofya, a huge Byzantine-church-turned-Ottoman mosque, and the Suleymaniye Camii, a gorgeously-constructed mosque. At the Chora Church, a 4th-century Byzantine chapel, Ersin, one of our ITU guides, gave me a Muslim perspective on Christianity when he pointed out one of the chapel's mosaics and said, "You know Jesus? He is very good doctor, I think." During our time in Istanbul we visited all of these and other sights, as well as one of the city's most elite clubs, a soccer match, homey traditional restaurants where we ate for less that $1, and the homes of some of our ITU friends. Yet, I was to come away feeling I'd barely scratched the surface of what this great, ancient city has to offer.

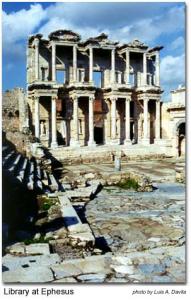

The next segment of our program was a nine-day tour around southwestern Turkey, focusing mainly on Greek and Roman historical sites such as Troy and Ephesus. We also traveled to the WWI battlefield Gallipoli and a nomadic village, as well as to the ancient cave dwellings of a Phrygian settlement.

article_492_order_2

Near the end of the trip we visited Pamukkale, a beautiful (though tourist-ridden) formation of calcium terraces formed by the flow of mineral-rich hot springs. It was here that we heard that passenger planes had just crashed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. On the silent bus, we watched the images on Turkish television of the dusty Lower Manhattan chaos. Back at the hotel we watched BBC World tight-lipped as the towers collapsed one by one. We tried (unsuccessfully, for the most part) to make calls to friends and family back home. I knew then that the America I had left in mid-August would not be the same one to which I would return.

Living in a foreign country with such a small group of fellow Americans had already forged some very strong bonds between us, and these seemed to strengthen even more in the ensuing days of uncertainty. It was difficult to see the group divide over the next few weeks: four people went home, two of us had earlier chosen to study at Middle East Technical University (METU) in Ankara, and the remaining seven elected to study at Bilkent University, also in Ankara. Those who left cited the probability of imminent war and its ramifications as their main reason for leaving.

As for the nine who stayed, we found ourselves in a calmer environment then we might have expected at home. The anthrax scares, the plane crashes and the war in Afghanistan were all somewhat distant to us. Although Turkey has in the past suffered terrorist attacks by Kurdish separatists, the problem was apparently solved with the 1999 arrest and imprisonment of their leader, Abdullah Öcalan. The Turks still employ visible anti-terrorist measures, however; we became used to passing through metal detectors in order to enter malls and bus stations and even came to appreciate these precautions in the wake of the attacks. It is certainly not the case that most Turks are U.S. sympathizers-some believe that America "got what it deserved" for what they perceive as its anti-Muslim foreign policy-yet at the same time none of us felt the climate there was threatening, and many Turks offered us their sincere condolences after the attacks. In short, although September 11 colored our study abroad experience, it certainly did not define it.

Personally, I found that the volatile world situation made me a much more avid reader of newspapers than I had been in the past. Some of the most widely available English-language papers in Turkey are the Turkish Daily News, which has a slight anti-American bias, the pacifistic British Guardian, and the American International Herald Tribune. I have no doubt that my easy access to different points of view, combined with the physical distance from the United States, allowed me to cultivate a more detached perspective on world events than I would have otherwise, and made me more inclined to question the appropriateness of my country's response to the attacks. Most importantly, I think, being among such hospitable Islamic people dampened any inclination I might have had to see the world in terms of "us" and "them". It is, however, impossible to know how much our opinions were actually affected by our circumstances. As John Van Way, a junior at Rhodes College and fellow exchange student, explained, "Sometimes I wonder if my displacement from American society has given me a more objective view of international events, or has contributed to my pacifistic leanings, but I'm not sure whether it's done either." Though John and I never reached any conclusions in our discussions about the war in Afghanistan and its possible escalation to Iraq, we did decide that the safest course of action for us personally would be to move to New Zealand and raise sheep-a determination strengthened, at least for me, when I came home via Paris only to find out that a man flying out of the same airport the day before had tried to detonate his shoes.

article_492_order_3

Despite international events, most of the interesting aspects of studying in Turkey had nothing to do with terrorism. For a start, there's the language, of Central Asian origin but infused with many Arabic and French words. Though not at all intuitive for English speakers, the Turkish language is exquisitely logical, and suffix-based. For example, to say "we will not come", one would simply intone "gelmeyecegiz," in which "gel-" means come, "-me-" is the negative suffix, "-yeceg-" denotes the future tense, and "-iz" means first person plural. I was interested to learn that the Turkish word for turkey (the bird) is "Hindi", or India. Though most of us in the program came here hoping to learn Turkish, our expectations ebbed gradually with our motivation. After all, at both Bilkent and METU all academic classes are taught in English, so the students speak our language (some more confidently than others). Most of us continued to take Turkish class once we reached Ankara, though for only four hours a week instead of fifteen as in Istanbul. We found that we knew enough to get us through basic interactions with campus staff and to order in restaurants; we became much more self-sufficient than in our first few weeks in Turkey. I even took a TaeKwon-Do class from a teacher who spoke no English, which felt a little like a game of follow-the-leader.

Of course, our interactions with Turkish students were not as comfortable as they would have been had we spoken Turkish well, but the Turks are famous for their warmth and hospitality, and we found that asking for help (usually for translation purposes or for navigating our new environment) often sparked a friendly conversation. We generally found that it was easier to make close Turkish friends in our dormitories than in our classes, highlighting the importance of choosing to live with a Turkish roommate. The twin barriers of language and culture made it much easier to associate with the American students to whom we had already been close, than to expend the effort to make new Turkish friends. Even so, I made a few friends in my TaeKwon-Do class, including a Jordanian student who told me that he was reconsidering his plan to do his Ph.D. work in the United States because of the international situation-an interesting parallel to the dilemma faced by our American friends who decided to leave Turkey early in the semester. I met two of my closest Turkish friends at Bilkent because they were dating my American friends, and our group of four Americans and two Turks grew quite tight-knit over the course of the semester.

One benefit of our acquired confidence with the basics of Turkish language and customs was our ability to take weekend trips from Ankara in small groups. Greek islands, beach resort villages, amazing archeological sites, and the famous rock villages of Cappadocia were all easily accessible.

article_492_order_4

For the "study" part of my study abroad, I chose to take two classes at Bilkent University, Turkish and Immunology. This afforded me four-day weekends during which I could travel. My immunology professor, like many professors at the University, was not Turkish. He was Bangladeshi, but I felt we shared a small bond because we were the only foreigners in the classroom. The immunology course itself was similar to what I was used to in my American science courses: lecture with plenty of student participation. However, coming from a small liberal arts college, the selection of courses available at Bilkent seemed comparatively huge.

There is so much of Turkey that I (often literally) only glimpsed in passing: the autumn-brown farmlands, the otherwise stark concrete structures with colorful rugs hung out for cleaning, the street vendors who somehow manage to eke out a living selling pastries, roasted corn, or nuts to passers-by for small change. My account has, I know, only scratched the surface in explaining the complexities of this country that is in many ways a crossroads yet at the same time undoubtedly unique. Yet I know that I could not have hoped for more. After all, we are the authors of our own experience. My time in Turkey was defined as much by my own personality and those of people around me than by the country itself.

Suggested Reading

Zakaria, Fareed. "How to Save the Arab World." Newsweek. 24 Dec 2001. 29 Dec 2001 http://www.msnbc.com/news/673522.asp

For additional information on study abroad in Turkey, the web address is: http://www.41colleges.org/turkey/studyabroad