Author: Katrina Outland

Institution: Hawaii Pacific University

Date: November 2004

The gray wolf. The Yellowstone wolves were removed in 1926 and reintroduced in 1995. Source: Oregon State University.

Why are so many images of fear symbolized by the wolf? From childhood, we shiver as the shifty-eyed wolf terrorizes Little Red Riding Hood and the three little pigs; Bram Stoker's Dracula opens with a wolf chase through a sinister forest; even the simple howl of the wolf is a symbol of something menacing and dark. The aversion towards wolves is easily understandable, but it causes a lack of objectivity about the wolf's real ecological role.

Perhaps this fairy-tale attitude of fear has made the wolves of Yellowstone National Park such a long-standing public issue, or maybe there is something more. After nearly a century of removing and reintroducing the Yellowstone wolves, the question remains: How well do we really understand this animal with such a storybook reputation?

First, a little history

The wolf issue has a history almost as long-lived as Yellowstone itself. In 1914, Congress approved funding to eliminate the native gray wolves from Yellowstone, fearing that elk and moose populations might be wiped out. By 1926, the last of at least 136 wolves in the park were killed, sometimes by controversial methods in themselves.

For nearly 70 years since, wolves remained absent until the National Park Service (NPS) proposed reintroducing them to Yellowstone under the Endangered Species Act. After years of debates, Congress approved the plan and 41 Canadian gray wolves were released in the park between 1995 and 1997.

The public speaks, and speaks again

Despite the plan's success, the boiling controversy has barely cooled. Before the wolves were even released, the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) filed a lawsuit against the Interior Department, claiming that introducing non-native wolves in Yellowstone using the Endangered Species Act was illegal. In retaliation, the non-profit organization Defenders of Wildlife accused the AFBF of wanting to kill the wolves, an accusation which AFBF vehemently denied.

The reintroduction is just as controversial among individuals as organizations. On one hand, the wolves have garnered many eager followers, such as this fan site dedicated to "wolf #10": http://www.angelfire.com/nj/wolf/. On the other hand, ranchers worry for their livestock and personal safety; others are concerned that the elk might be killed off.

Clarice Ryan, a resident of Bigfork, Montana, told reporters in 2003, "[The wolf] decimates the wildlife population wherever it goes. This animal alone has the ability to jeopardize our entire way of life."

It seems there is little room for a middle ground.

Are the elk in danger of extinction?

Elk: the primary prey of wolves. Many fear that wolves will decimate the Yellowstone elk population. Source: Oregon State University.

A primary complaint is that the wolves may endanger the elk population and other prey.

"We are going to run out of elk in somewhere between 5 and 10 years," said Gary Marbut, president of the Montana Shooting Sports Association, in an interview in 2003. Before the reintroduction, computer models predicted that the elk population could be reduced by 8 to 20%.

However, not all scientists agree. Elk counts published in the January 2004 issue of the Journal of Wildlife Management reported that elk populations from 1995-2000 were more influenced by the winters than the rising wolf population. In addition, a study in 2001 showed that Yellowstone moose whose offspring had been attacked by wolves learned predator recognition within a single generation.

"Mechanisms for predator avoidance are already in place, and fears of imminent extinction may be unwarranted," said Joel Berger of the University of Nevada, the study's lead author.

My, what a long reach you have

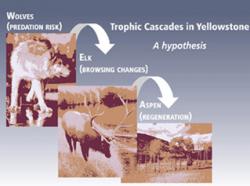

A wide impact. Wolves may affect the food chain all the way down to the tree level. Their presence changes elk feeding behavior, which influences aspen sapling growth. Source: Oregon State University.

With all the divided opinions, it is hard to find an objective analysis of just how the wolves affect the environment, and whether they are needed or not. Because their reintroduction is fairly recent, scientists are just beginning to grasp the actual ecological role of the Yellowstone wolves.

In 1997, researchers including William Ripple from Oregon State University noticed that the aspen trees in Yellowstone were dying. By counting the rings from core samples, they found that the aspens have not regenerated since the 1930's,shortly after the wolves were eliminated.

"Predation by wolves can have a big impact on the ecosystem," explained Ripple, who has published several articles on the relationship between wolves and aspen growth. "The wolf as a keystone predator will prey on elk, and then the elk eat young aspen, cottonwood, and willow trees. Now with wolves back in the system, the plants are flourishing more than before."

Ripple's collaborator Robert Beschta, also of Oregon State University, has found similar results in the cottonwood trees. He discovered the effects of a process called atrophic cascade, in which an organism at one end of the food chain affects all other organisms in that ecosystem. This means that wolves not only decrease the number of elk, but also change their behavior. Elk tend to avoid areas frequented by wolves, which include aspen thickets. This may, in turn, protect saplings from being eaten.

"When the wolves disappeared from Yellowstone, the saplings stopped growing up into mature trees," said Beschta.

The trees in turn have a wide-reaching effect on the rest of the ecosystem. With signs of plant health improving, Ripple was optimistic:

"We might see more birds, an increase in beavers, which would create more ponds, which creates more habitats . . . there's all types of cascading effects that we're starting to document with the reintroduction of wolves."

A new controversy: delisting the wolf

Eight years later, the debate is far from over. A move to take the wolves off the Endangered Species List has again stirred arguments. The state legislatures of Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana claim they want federal management of the wolf populations to be turned over to the state. According to Rep. Jim Allen of Wyoming, the federal government should "keep wolves inside Yellowstone because they don't have legal jurisdiction to release wolves in Wyoming, only the state does." Yet, the proposal of Wyoming's House Bill 229 and Montana's HB 283 in early 2003 re-stirred public emotions that run much deeper than jurisdiction concerns.

Many supported the de-listing, which would allow anyone to shoot wolves outside of Yellowstone at any time. Local ranchers fear for their livestock. In 2000, Yellowstone wolves killed at least seven cattle, 31 sheep, and five dogs. Some ranchers such as Alan Rosenbaum from Moran, Wyoming feel intimidated by wolves living so close.

"I need protection for my family," Rosenbaum said at a meeting to discuss HB 229 last year. At the same meeting, rancher John Robinette said that a wolf even attacked one of his dogs while his wife was walking it. Several people complained that any wolves in the state are too many.

The environmentalists present another argument. A study published in 2003 by the Wildlife Conservation Society reported that wolves should not be de-listed because they may not be fully recovered.

"When humans have tried to eliminate wolves in the past, there have been severe consequences," said Beschta, explaining the ecological perspective.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said that Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho must have approved wolf-management plans before the wolf can be de-listed. Wyoming has yet to do so, and the dispute carries on.

Where do we go from here?

It is hard to say why the wolf reintroduction is fought over so ardently by so many. Maybe the wolf's reputation for fear extends beyond literature; maybe pictures of cute and fuzzy pups have triggered protective responses from animal lovers. Either way, the real-life ecological role of wolves is poorly comprehended and under-represented in public forums. In a complex issue where accusations and insults fly all too freely, progress can only be made on a common ground of education and mutual respect: respect especially for an animal that never deserved to be so misunderstood.

References and Suggested Reading

The Official Website of Yellowstone National Park: http://www.nps.gov/yell/nature/animals/wolf/wolfrest.html

The Yellowstone Wolf Report Page: http://www.yellowstone-natl-park.com/wolf.htm

Wolves in Nature by Oregon State University: http://www.cof.orst.edu/wolves/